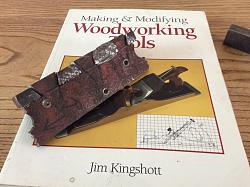

The book in the picture is “Making & Modifying Woodworking Tools” by Jim Kingshott. He recommends practising the technique of dovetailing, before embarking upon making a plane. You can see that I have begun my practice piece, using bits of scrap. I have never cut dovetails in steel before. To fit them, you have to leave excess on the tails, and peen them to fill the gaps, not like you would fill the gaps with glue and sawdust. (Note irony)

Trouble is, the more you hammer, the more the sides bend in. Can you make out the gap? It’s distorted by 2 degrees, and I have peened only one pin.

Kingshott recommends packing the body with hardwood, and clamping it firmly in the vice.

I would say that this is an abuse of a bench vice, so I clamped to an anvil, but significant movement and damage occurred to the packing, so next time I shall pack out with steel.

Kingshott also says that you don’t want the mouth adjacent to the tail, because this cuts the sole right acrossBut this is view of my piece is on the page showing his mitre plane. The sole is cut right across.

I would be glad to hear the views of people who have made these type of planes. During lockdown, I plan to make three.

The book was given to me by Bob Eades. He was a master joiner, and I mean really top-notch. His hobby was reproducing Guarneri violins. He brought a Holtey plane along to the meeting of the Carpenters’ Institute. Holtey planes are dovetailed, superbly refined. Bob told us it had cost him £2000. It was our chairman who observed that, with such precision, it was no good trying to fill the gaps with glue (as if we ever would)

Bob knew of my interest in plane making. He lived in my road. I met him shortly afterwards, saying I had made a plane and he invited me round. When I got there next week, there on his coffee table were 14 planes, every bit as good as the Holtey plane, ranging in size from 8” down to an inch, they were mostly for violin making. Well, I never showed him the sandwich I’d bodged together!

LinkBack URL

LinkBack URL About LinkBacks

About LinkBacks

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Bookmarks